Translating my Grandfather’s biograpy

My grandfather, Dr Kornelis Sietsma was a Dutch Reformed Church minister in wartime Amsterdam. He preached in ways that offended the Nazi occupiers, and they deported him to the Dachau concentration camp, where he died.

This was a fascinating family history to me growing up - I was named after my grandfather, and his heroic attitude and tragic death informed my view of the world.

Now I have kids of my own, and I started thinking about how I could explain their great-grandfather to them. I knew quite a few broad facts, but hadn’t dug into the specific details. Also information about him is scattered all over the place, and is mostly in dutch - there’s a dutch Wikipedia article for example, but no English one. I thought it’d be good to start building something I could put on the sietsma.com website.

One important source I knew of was a short biography, written by a colleague of Dr Sietsma in 1946. It was titled “Een Waarlijk Vrie” which translates as “a Truly Free person” - and I already had translation made by my Uncle Arie in the 1990s. I thought of just putting that online, however, looking at it, it was quite wordy and hard to read. I could have cleaned it up and simplified it, but I didn’t feel confident just altering his translation, I thought it’d be good to cross-check it against the original dutch text.

It also occurred to me that this could be a good use of a modern Large Language Model based AI. I’m rather skeptical about LLMs in many cases, but this seemed one of the areas they might really add value - there’s a lot of data to build on for translations, and in this case I could check the results - both against my Uncle’s translation, but also I have Dutch speaking friends who could double check specific parts.

So I hunted online and found I could buy the book from a second-hand dealer in the Netherlands - a few days later it arrived:

I now needed to turn it into text - a bit of digging and I found that Mac OSX has built in text recognition (OCR) tooling - you can just load a picture into Preview or the Photos app, select some text, and copy it into a document.

So I scanned it in - you can read the Dutch version of the book here though as I don’t read Dutch it may have mistakes! I did have to do a lot of manual work as well - mostly things like handling unusual letter pairs like ij, and long words split at line endings with hyphens. But the Mac OCR tooling did most of the hard work.

And then I went looking for good translation options. The main tools I used were DeepL, a set of translation tools using an LLM based engine, and Claude a more general purpose LLM AI. (There are many others to choose from - I used these as I had friends who recommended them and they both had good reputations).

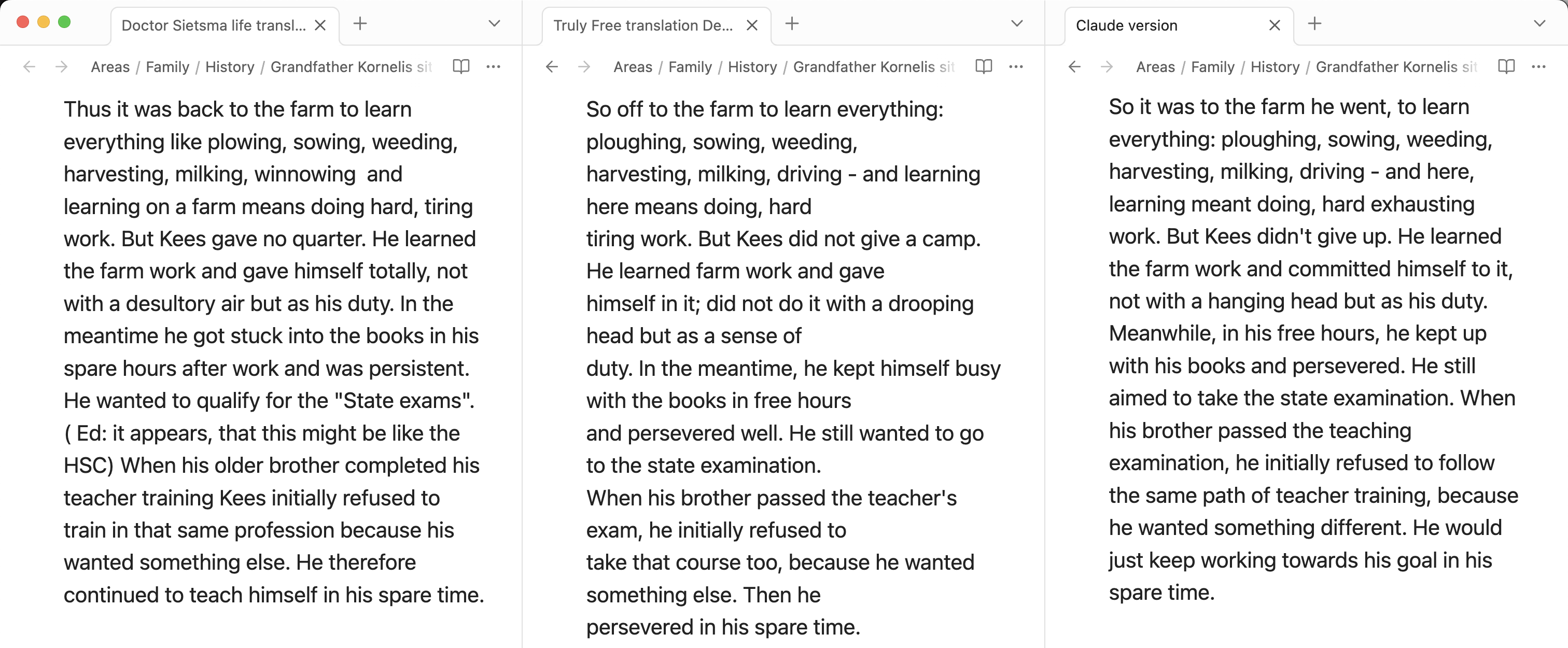

I then spent some time looking at the versions side-by-side, using Obsidian as it works not just as a note taker, but also is a quite good markdown editor. And slowly I built up my own version from the 3 different sources:

The results were surprisingly good. Not perfect - in some cases Arie’s translation was clearer, in some cases there was disagreement and I had to check with friends who read Dutch about which idiom was correct. In some cases the LLMs just returned literal word-for-word translations which didn’t make much sense.

I also found the LLMs quite inconsistent with place names - in some places a church is “Amsterdam South”, in others “Amsterdam-Zuid” - something a human would probably notice and catch. (I haven’t cleaned all these up - it probably needs another human pass!)

On average Claude did somewhat better than DeepL. I think that’s largely because I could give it a specific prompt, to tell it that the text was 1940s Dutch, which helped it do a better job at translating dated terms and idioms. For reference this was the prompt I used:

I have a biography of my grandfather written in 1946. I need your help to translate it accurately so that his original meaning and intention is preserved. Please take note of the approximate time period as Dutch is likely to have been spoken in an older style than today. I would like it translated into a modern British english style.

Claude also inserted explanations about some key points, which was sometimes useful where there was ambiguity or specific references - I used these explanations to add a lot of footnotes to the final translation.

The main place both LLMs struggled was with idioms and archaic expressions. One example from grandfather’s childhood: (key differences in bold):

Dus naar de borderij om alles te leeren: ploegen, zaaien, wieden, oogsten, melken, mennen — en leeren beteekent hier doen, hard vermoeiend werken. Maar Kees gaf geen kamp. Hij leerde het boerenwerk en gaf zich ook daarin; deed het niet met een hangend hoofd doch als zin plicht.

My uncle translated this as:

Thus it was back to the farm to learn everything like plowing, sowing, weeding, harvesting, milking, winnowing and learning on a farm means doing hard, tiring work. But Kees gave no quarter. He learned the farm work and gave himself totally, not with a desultory air but as his duty.

but DeepL was a bit different:

So back to the farm to learn everything: ploughing, sowing, weeding,

harvesting, milking, driving - and learning here means doing, hard

tiring work. But Kees did not give a camp. He learned farm work and gave

himself in it; did not do it with a drooping head but as a sense of

duty.

Claude was different again, but with some extra notes:

So [I went] to the farm to learn everything: plowing, sowing, weeding, harvesting, milking, driving [horses or cattle] — and learning here means doing, hard exhausting work. But Kees didn’t give up. He learned the farm work and devoted himself to it; he didn’t do it with a hanging head but as his duty.

- “Mennen” refers to driving or controlling horses or cattle, a common farm task at that time.

- “Gaf geen kamp” is an idiomatic expression meaning “didn’t give up” or “persevered.”

- “Zin plicht” is likely a misspelling or older form of “zijn plicht,” meaning “his duty.”

- (I checked the original and indeed it was an OCR failure, the original book had “zijn plicht”)

It was interesting here which to choose. My uncle in this case had gone for more modern idioms (though it seems ‘winnowing’ was probably a mistake). “Gaf geen kamp” was translated literally as “gave a camp” by DeepL, converted to “didn’t give up” by Claude, and “gave no quarter” by my Uncle. I checked this phrase with a Dutch friend and he confirmed that Claude was probably best here, and it’s an old idiom not in common use these days.

As an Aussie I ended up using “droving” for the first word - it is apparently an English word originally but quite common in Australian history and folk songs.

My final version of this section was:

So it was back to the farm he went, to learn everything: ploughing, sowing, weeding, harvesting, milking, droving - and learning here means doing, hard tiring work. But Kees didn’t give up. He learned farm work and committed himself to it; not grudgingly but with a sense of duty.

As I worked my way through the book I found quite a few more translation differences - but they were mostly small. A few things each of the AIs failed to translate, or translated literally like “give a camp” above, but generally I was impressed how well they did - nothing was outrageously wrong or hallucinated.

I’ll share one more example, which was quite significant given it was a passage from my Grandfather’s final sermon, and was the particular topic the Nazis used to justify his deportation:

De prediker bracht den Christus in het licht in zijn heiligen, principieelen strijd met den Satan; deed ook uitkomen, dat de Satan nog de machtsverzoeking wel toepaste en dat hij zocht te verleiden met de koninkrijken der aarde.

The tenses here are interesting. My uncle translated this as:

The preacher brought Christ to light in his holy, principial battle with Satan. He made it clear that Satan applied the temptation of power and sought to seduce Him with all the kingdoms on earth.

But Claude (and DeepL) seemed a bit different:

The preacher brought Christ to light in his holy, principled struggle with Satan; also made it clear that Satan still applied the temptation of power and that he sought to seduce with the kingdoms of the earth.

That “still” seems to suggest that this is an ongoing temptation by Satan; rather than something that just happened in biblical times. And so “he sought to seduce” applies to modern people, not just to Jesus (as implied by the “Him” in the first translation).

I asked Claude to elaborate, it replied:

In the original Dutch text “dat de Satan nog de machtsverzoeking wel toepaste,” the word “nog” (still) combined with the past tense “toepaste” (applied) creates an interesting temporal meaning.

From the context, this appears to be describing Satan’s actions during the time period that the preacher was discussing (likely referring to the Biblical temptation of Christ) and extending to the time when the sermon was being given (1942). The use of “nog” (still) suggests a continuation of this behaviour from the Biblical past up through the time of writing.

Again I checked this with a Dutch speaker, and they replied:

… I wanted to confirm that Claude is correct in their explanation. The original text suggests current and ongoing temptation.

During Dr Sietsma’s interrogation by the Nazis, they asked whether the “temptation of power” could also be found in National Socialism (Nazism) - he said that it could. This was the key point they used to send him to Dachau concentration camp.

I made a few other changes to the text - trying to retain the facts and the message of the original. The text referred to my grandfather occasionally as “Kees” (which is what people called him) but more often “Sietsma” or “Dr Sietsma” - I converted most of these to “Kees” as I felt it made the language more personal and direct for a modern audience.

I also broke up long paragraphs, and added more headings to make navigating the text easier. The book has some very long passages about his sermons and writings, and I suspect many people would like to jump straight to the wartime section! Though the rest provides some great background and context.

I also added maps and images, and quite a few explanatory footnotes, some based on Claude’s notes and some where I thought a phrase might not be obvious to a younger audience, not brought up on terms like “National Socialism”.

My finished translation is at https://sietsma.com/dr_k_sietsma/een_waarlijk_vrie/2024_translation/ - there’s an overview page with the Dutch text and other comments at https://sietsma.com/dr_k_sietsma/een_waarlijk_vrie/.

This was a fascinating exercise - both to learn more about my Grandfather, and also uses of modern AI tools. It reinforces that they can be extremely useful in cases where you can verify the results, and adjust any errors.

This is similar to what I’ve found using Copilot and other AI based software tools - I wouldn’t trust them to write code unsupervised; even when they are ‘correct’ they often produce poor quality code that could easily become a maintenance nightmare. But when you can check the results and adjust by hand, they can be a very helpful tool.